Analysis: Border conflicts in Northeast India and how they came to be

For the uninitiated, the Northeast brings to their imagination the same violent exoticism that the more familiar Red Corridor does. There are seeds of truth and poisonous lies woven in these shifting stories, but at the centre of it lies a larger unsolved story — the border conflicts within the northeastern states.

Let us go back to August 12 to 14, 2014, for example. An ordinary time in Indian history, save for a small band of Naga political groups who raided a stretch of forest near Uriamghat in the Golaghat district of Assam. Golaghat district has been the centre of heated clashes between Nagas and so-called “recent encroachers” — an assortment of advisasis, tea tribes, Assamese, and Nepalis.

Years of extortion and kidnappings from the Naga side eventually culminated into the murder of nearly 17 Assam residents, with hundreds of huts burnt and over 10,000 natives displaced, all under the eye of the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF). Yet the city of Kohima, at a mere distance of four to five hours from Golaghat, is a peaceful picturesque city that might even bore its residents on some days.

These events barely capture the string of inter-ethnic clashes that trace the dense borderlands of the Northeast. Indeed, the Northeast is among the most important frontier regions in India, bordering China, Bangladesh, and Myanmar. In its origin lies a rich tapestry of parallel and overlapping histories of kingdoms and clans in the South-East Asian Massif that have come to define its “separateness” from Indic heritage. Its modern conception, however, is rooted in British colonialism and post-Independence bureaucracy.

Much of the conflict over its borders is a struggle between the “defined” and “undefined” — between the dichotomy of borders and the narcissism of small differences among borderland communities. It is the penchant for a tempting exclusionary rule; the disease of excessive historicism; and the building of great “emotional borders” to cement artificial state borders.

A large part of the Northeast today was carved out of Assam, a region that territorially expanded under the British. Throughout the nineteenth century, successive British administrations have moulded tribal frontier lands with Assam at the centre. One such tribal land is the home of the Nagas. Beyond myth and folklore, the history of the Naga people is blurry.

As disparate sovereign clans and village states, they settled the Naga Hills much earlier than the movement of Ahom settlers into the subcontinent. But the events that have most triggered a composite identity among the Nagas is the 1866 creation of the Naga Hills District, and by 1912, its inclusion into Assam Province. In 1870 particularly, the subdivision of North Cachar Hills, home of the Zeme Nagas (but also home to Kukis and Kacharis, among others — a detail often forgotten), was demarcated into Assam. These strategic experiments by the British required Naga-inhabited lands to be shuffled around without the consent of the region’s inhabitants.

In 1963, as a result of a treaty between the Nagaland People’s Convention and the then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, the Nagas were freed from the yoke of Assamese domination and received statehood.

Yet, successive Naga leaders and the government have felt that people have been repeatedly short-changed. Since the 1940s, the Nagas have demanded complete independence from India, while also disputing the post-statehood boundary with Assam, pitting constitutional rights against historical rights over fertile lands. This border stretches a mere 434 km, with four of six sectors contested by Nagaland. These include Sivsagar, Golaghat, Jorhat, and Karbi Anglong. At heart are 66,000 hectares of land, all fertile, both forested and un-forested.

From the 1960s to 1970s, the Naga-Assamese borderlands have been marred by violence, with over 20,000 already displaced and hundreds killed in clashes and raids by insurgent groups and administrative authorities. Over 3,000 people are now directly affected by the borderland conflict. At the height of this violence, Nagaland rejected the recommendations for a borderline under the Sundaram Commission, which culminated into a Supreme Court case in the 1980s that remains pending to this day.

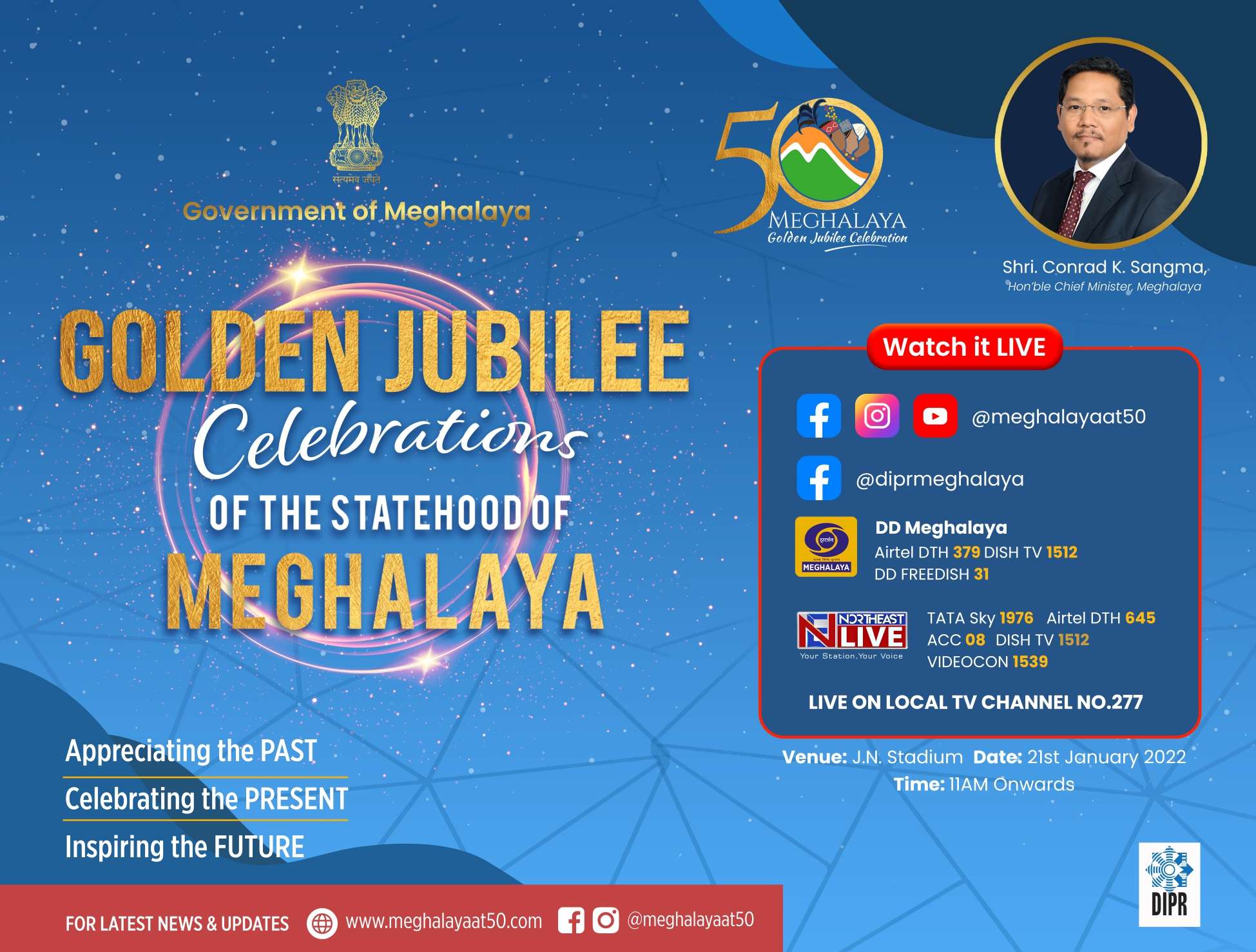

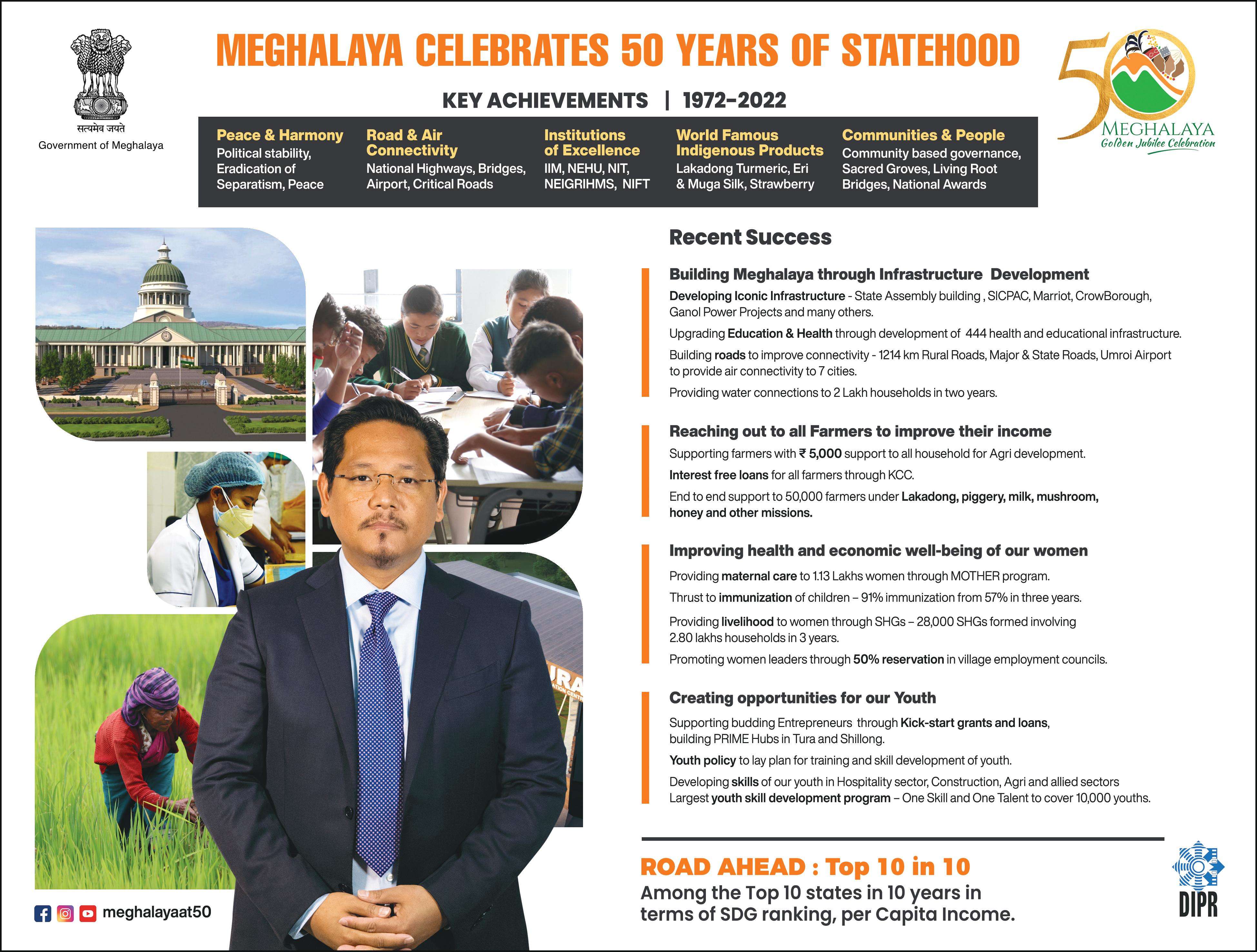

To the south of Assam lies Meghalaya, which shares a vast tract of 2,700 sq. km. of land with Assam. It contests the ownership of the State Guest House of 1976 – where the chief minister of Assam now sits – as well as Upper Tarabari, Gazang Reserve Forest, Hahim, Langpih, Borduar, Khanapara-Pilangkata, Deshdemoreah Block I and II, Khanduli, and Retacherra.

Since achieving statehood in 1972, borderland communities have borne the brunt of inter-ethnic conflict and state police violence, such as the 1974 violence against the minority Nepalis residents of Langpih, which borders Assam’s Kamrup district. Like most conflicts within the Northeast, Meghalaya and Assam’s grievance is selectively historical — a fight over which political map is more legitimate.

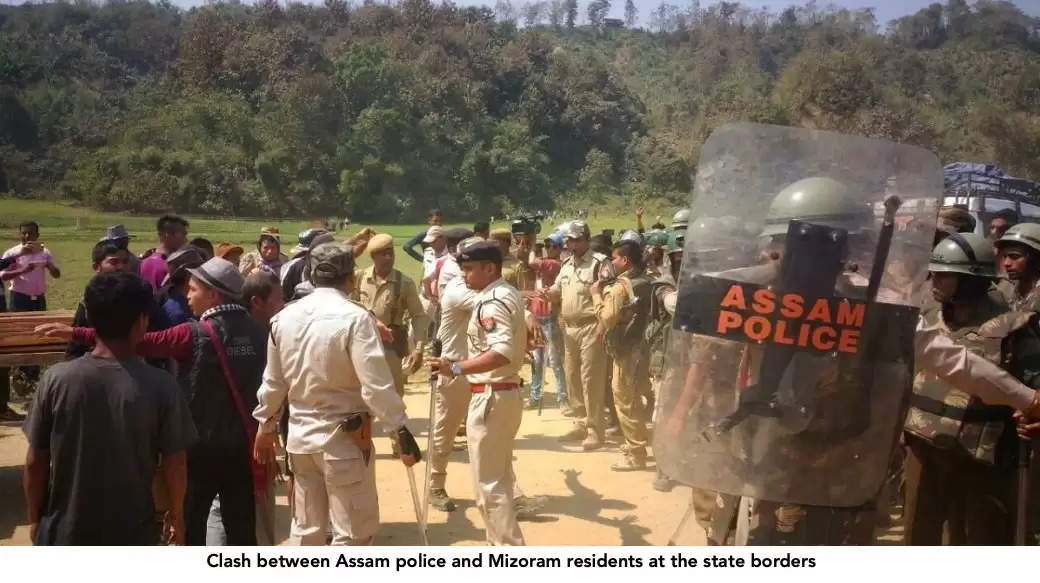

In 2019, the Assam police under the jurisdiction of the Hahim Outpost sabotaged the construction of a road under the Prime Minister Gram Sadak Yojana in Ranighat village in the Rambrai–Jyrngam constituency of West Khasi Hills. Construction material was vandalised, forcing the poverty-stricken residents, mostly Khasis and Garos, to agitate against the police’s heavy-handedness in denying them access to education, healthcare, and markets. A year later, Assamese residents, in turn, accused Khasis of blocking road construction and “encroaching” the disputed Langpih.

A tenser battle also rages between Assam and Arunachal Pradesh, with a Supreme Court suite pending since 1989. Clashes continue to erupt periodically between Arunachali tribals and Assamese villagers. In August 2010, for example, Isak-Muivah militants of the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN), along with Arunachali tribals, raided Saraipung village in eastern Sivasagar district for allegedly encroaching into Arunachal Pradesh.

To the south-east of Assam, the Manipuri Maos and Angami Nagas have festering relations over the ownership of Dzüko valley. Both states lay exclusive claims to territory, often imposing debilitating economic blockades against each other by clogging national highways that run like arterial lifelines through their respective states. Conflicts frequently arise in Ukhrul district, Jessami in Manipur and Meluri, Phek in Nagaland, which lie adjacent to each other.

Also, neighbouring Assam is Mizoram, which became a union territory in 1972 and then a state in 1987. Yet, the relatively short 164.4 km border between both states has become the object of borderline obsession, particularly across Kolasib, Mamit, and Aizwal versus Cachar, Hailakandi, and Karimganj of Assam’s Barak Valley. The five decades since 1972, tensions have risen and fallen.

What were once borderless fuzzy distinctions between neighbouring groups, have become accepted differences that need to be “resolved”. While the Mizoram Students Union has recently taken the route of laying these tensions at the feet of undocumented migration from Bangladesh, the grievance predates the spectre of “the foreigner” and the desire to return to the East Bengal Frontier Regulation of 1873 to demarcate boundaries.

As recent as October 2020, Karimganj district officials, the Assam Forest Department, and the Assam police were accused of razing a betel nut plantation in Thinghlun village in the contested Mamit district of Mizoram.

Tensions have also flared between Mizoram and Tripura, such as in August 2020, in the disputed Phuldungsei village in Jampai Hills along the Tripura–Mizoram border, when the Bru Songrongma Mthoh were stopped by Mizos from building a Shiv temple, leading to prohibitory orders being imposed. The Bru-Reang tribals, who have historically inhabited stretches of land spanning both the modern states of Tripura and Mizoram, have had to flee after repeated ethnic cleansing by Mizos. They are now among India’s internally displaced refugees.

A Return to Origin or Dubious Revivalism?

Because so much of Northeast was once under Assam, the Assam state and police are often seen as the aggressors, playing the inheritors of a colonial policy that demonised highland tribes as barbarians that threatened commerce and real estate. But the violent policing of tribals and non-tribals has been the business of each state, whilst borderland communities themselves fight over spurious claims.

In 1959, Alexander Mackenzie, a British administrator, stressed the need to reign in the upland tribes of this region. The product of these suggestions was the Inner Line Regulation, which came into effect on March 7, 1873. Its successor is the infamous Inner Line Permit, a prized isolationist policy that restricts entry of non-residents into select northeastern territories in the hopes of providing demographic security.

The original intent of the regulation was not so much to protect the integrity of international borders or vulnerable cultures but to control the “antagonistic” highland tribes. The regulation allowed the colonial administration to ensure their commercial interests were protected and the acquisition of tribal land was smooth for oil, mineral, and other resource exploration. A real estate legislation, in essence, was part of the British conception of the Northeast as a region of “the plains people” versus “the hill people.” These distinctions also informed their bordering decisions.

For instance, in a 1951 notification, a 716 km boundary was demarcated between the North-East Frontier Tracts — a political division then — and Assam, which forms the basis of the boundary of Arunachal Pradesh today. At the time, the British transferred large tracts of plains to Assam, parts of which are a spectacle of inter-state conflict. But amidst these strategic demarcations and arbitrary ahistorical dichotomies, the desires of borderlanders have been ignored, starting from one annexation to the next and from one demarcation to the next.

The modern ideology of the “nation-state” now demands that each state form its own sub-national identity, one rooted in territorial exceptionalism, supremacy, and dichotomies. The question persists: Are the northeast’s border disputes themselves a colonial hangover? Are they a dubious attempt to create a homogeneous identity out of distinct tribes?

(Edited by Anirban Paul)