A new hope for Meghalaya to make it back into Indian cricket’s mainstream?

By Sharda Ugra, Senior Editor, ESPNcricinfo

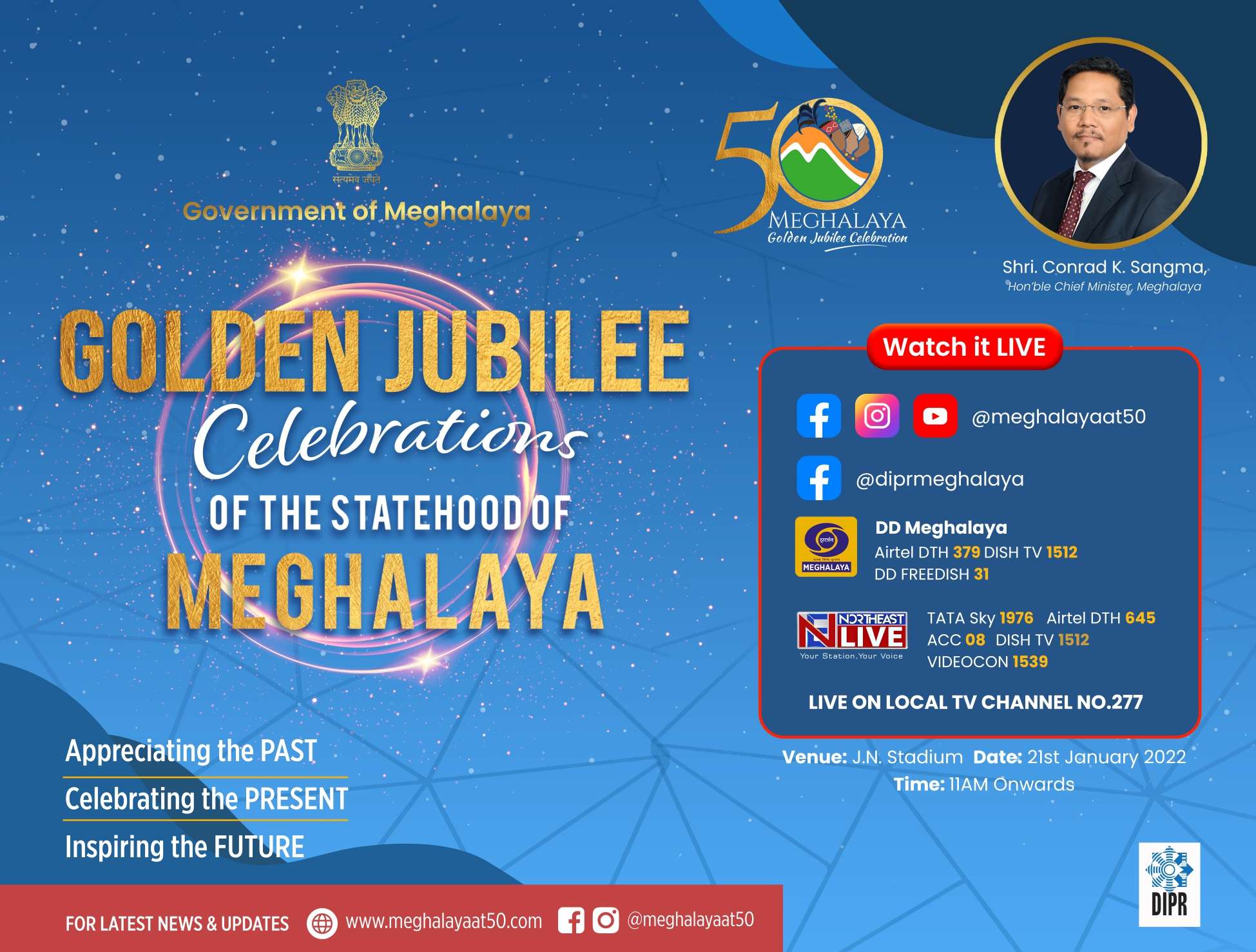

It is a crackling October day in Shillong. Traffic and noise whirl around the Polo Bazaar. The FIFA Under-17 World Cup is being played around India and there's a Shillong Premier League match scheduled in one of the football grounds at the entrance to the Jawaharlal Nehru Sports Complex.

Inside the gates, the hulking terraces of Nehru Stadium echo with the sounds from a girls' inter-school football match. Their voices cut through the air, ringing out across the tennis and basketball courts on one side and the small houses rising up the hillside on the other. There is another group across from the tennis courts, on another field, making less noise, getting less attention, but hard to ignore.

"Move, move!" It's the umpires yelling, trying to get the fielders to begin prowling towards the batsman as the bowler runs in. Catching a glimpse of organised cricket in India's north-east can at most times feel like a Yeti sighting. This is a region obsessed with football, where about 3% of the country's population has supplied around 30% of India's professional players in its highest leagues.

Yet, cricket in Shillong should not look incongruous, because, well, this is a town that rarely falls in line with presumption, assumption or convention. It is the capital of Meghalaya, a place where Iron Maiden and Guns n' Roses rock out loud from the taxis. They don't exactly go with the flow here, and so, despite the region's historical detachment from cricket and fondness for football, we have the unique story of Shillong cricket.

Until 1973, the city was the capital of undivided Assam. Cricket was first played there by British officers and sahibs in the 1860s, and the Shillong Cricket Association was founded in 1937 (the same year as Baroda's and a few years after those of Madras, Hyderabad and Mysore). Assam's first Ranji Trophy match was held in Shillong in 1948, at the Garrison Ground. The town has had a long-established club cricket league, which currently features 14 teams in the Super Division, 42 in the First Division, and 19 in B Division.

The schism between Shillong cricket and the Indian mainstream came into being with the creation of the new north-eastern states from Assam, and the moving of Assam's capital to Dispur. The Meghalaya Cricket Association (MCA) ground today occupies a space a fraction of its original expanse, having ceded territory to the rest of the Nehru sports complex, which is dominated by the multi-sport Nehru Stadium, home to the Shillong Lajong football club. But the cricketers skittering around the MCA ground in October 2017 have been once again hooked into the bloodstream of their sport.

The players being asked to move are from the first Meghalaya U-19 women's team. The majority of them are drawn from the neighbouring countryside and are about to be pitchforked into an U-19 regional competition with zero experience. It has been just a few weeks since their formal introduction to cricket itself, which came about because the Justice Lodha recommendations to the BCCI mandated that junior and women's teams from the north-east ought to figure in the mainstream, starting with the 2017-2018 season.

Everyone knew the girls were going to get beaten when they travelled to Dhanbad for a north-east and Bihar women's U-19 event in November. But the MCA sent the team over anyway – to see what life was like on the other side, to understand how far behind they were, to experience other parts of their country, to take planes, stay in nice hotels, and see what could come of sticking to cricket.

****

Smriti Gurung knows. "I want to pursue cricket in my life, make it my career." She is 16, bespectacled, the most skilled and well trained of the Meghalaya U-19 women, and has been under formal coaching and training for over three years.

Gurung dived into cricket after being swept up by India's 2011 World Cup victory, playing the game with her brother and other boys in the neighbourhood in the Assam Rifles compound. (Assam Rifles is India's largest paramilitary force, headquartered in the north east. Gurung's father is a Rifleman.) Within a year of picking up the sport, she had fractured her arm courtesy a flailing bat. After she and her family moved out of the compound, she was given permission to return to play in the parks there.

"I didn't know there was an academy in Shillong. I didn't know where girls could play." When she found out, she turned up and asked to be admitted. A few times. When they finally let her in, when she was about 13, she was the first girl in the Shillong Cricket Academy, and was made to play with much younger children before being elevated through age levels ("double promotion"), into training with the U-16 and U-19 boys. She led the team in Dhanbad, which was, she says, "a first time for everyone, so a good lesson After the first match, [which Meghalaya lost to Sikkim] everybody was crying."

The Meghalaya U-19 women, with 13- and 15-year-olds in the travelling party, then scored their first victory, against Manipur, and earned praise for their fielding.

Dhanbad was a reality check, but the bug has bitten many and they know there are others like them. Gurung's favourites? Harmanpreet Kaur and Smriti Mandhana, she says instantly and adds, as an afterthought, "and of course, Virat [Kohli] and Hardik [Pandya]".

A couple of youngsters in the nets, with houses in the Pynthorbah locality in the backdrop Sharda Ugra / © ESPNcricinfo Ltd

Only two cricketers from Meghalaya have played first-class cricket – and that was for Assam. Shillong district used to participate in Assam state competitions, which led Mark Ingty and Jason Lamare into the Ranji Trophy competition. Ingty's domestic cricket career, which ran from 2001-02 to 2006, also featured a Duleep Trophy appearance for East Zone. Peter Lamare, coach at the Shillong Academy, was involved in both men's careers, as father and uncle. A club and district player, Lamare senior says his generation,couldn't "look so far" during the 1970s and 1980s. Shillong district's presence in Assam wasn't exactly actively acknowledged or encouraged. "We didn't have the facilities or the ground or the motivation, because nobody backed us."

On that afternoon in October 2017, it was Lamare, a coach trained at the National Institute of Sport, who shouted at the U-19 girls to move. The creation of the team, he says, was both adventure and lark. Trials in Shillong had not produced enough girls of the age group they needed, so along with his MCA colleagues, Lamare travelled to the small towns of Mairang and Noingstoin, where they shortlisted 22 and then 17 girls to play cricket.

The kids were familiar with cricket off television but had to be taught the basics – how to hold the bat, the stance, the backlift, footwork – for a little under a month before being dispatched to Dhanbad. "We are teaching them the basics and they are going to represent the stage, I can't believe it," Lamare said. "But it is a big beginning for us, it's a big beginning for them."

****

Meghalaya's senior men's team, on the other hand, says MCA secretary Naba Bhattacharjee, could beat regular Ranji wooden-spooners Tripura. Meghalaya must, however, wait for a direct entry into first-class cricket, and can compete only in juniors and women's events. The Lodha recommendations mandating one vote and one team for every state means that this season the north-east teams had to be shoehorned into the circuit. The boys' U-16s and U-23s and the women's U-19s were to make tumultuous debuts across all formats.

Each of the six north-eastern teams (Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Mizoram, Meghalaya, Nagaland and Sikkim) and Bihar first played each other in a north-east zone, with the top two teams then going up for the national competition against other state squads. The U-19 boys' team is currently competing as a combined Associates and Affiliates team in the Cooch-Behar competition. A road map for the senior men's and women's teams for the seasons ahead is yet to be drawn.

The women's competition produced scorecards that horrified the purists. Manipur sent down 94 no-balls versus Nagaland in Dhanbad, and Nagaland themselves, who qualified for the Super League, the upper tier of the women's zonal U-19 tournament, were all out for 2 versus Kerala in Guntur. Yes, the cricketing standards of the north-eastern teams are low when compared to the "mainland" teams, but the appearance of such scorecards in the richest and biggest cricketing country on earth told a tale: of lopsided development and of the uneven spread of the BCCI gospel, ten seasons into the IPL and almost 20 years after the first of the big TV deals came along.

A couple of batsmen polish their high-elbow technique at the sports complex Sharda Ugra / © ESPNcricinfo Ltd

"People keep saying there is no talent in the north-east, and I say that is chicken-and-egg stuff," says Bhattacharjee, "We have to get the opportunity, you have to create the infrastructure, pitches, grounds, nets, coaches, and the talent will come." In 2014, Bhattacharjee, a third-generation Shillonger, convened a six-state North East Cricket Development Committee to push regional causes and presented the BCCI with an approach paper focused on support and funding. "We told them, we don't want Rs 15-20 crore [about US$2.7 million] but from the IPL surplus you could give us one or two crores so we can start."

For the MCA, the Lodha report has provided a touch of serendipity. But how on earth can the BCCI be expected to work with states that have (outside of Shillong) zero in terms of cricket outlook or mindset?

Actually, it is not so complicated. The BCCI could resume from where they themselves left off circa 2012. Around 2007, a committee was created to explore "new area development", which included the north-east. Stanley Saldanha of Tata Consultancy Services was hired as Manager, Game Development, and his New Area road map ought to still be valid. The document began with a focus on junior cricket and looked at the creation of training and job opportunities in other areas of cricket, including umpiring, online scoring, video analysis and ground management.

The better north-eastern teams, such as Meghalaya, Manipur and Nagaland, began playing events involving themselves and sides like Bihar and Chhattisgarh, one state represented by one team. Training programmes and exams were held for umpires and scorers, so that the best candidates could be trained for BCCI-level courses. Coaching camps and courses were held (in Shillong, as it was a central and convenient venue) and five talented cricketers were selected and sent to the National Cricket Academy in Bangalore for training. The BCCI also purchased cricket equipment worth Rs 20 lakh for each state.

Saldanha, who worked actively with Bhattacharjee during his three-year tenure, left in 2010, largely due to familiar internal issues. The board's interest in its noble but complex north-east mission began to run out of gas, and there was little impetus being provided by the most powerful officials at the top. There were also, of course, a few familiar hurdles: in 2010 it came to light that Rs 25 lakhs from grants given by the BCCI were transferred into an official's savings bank account, and used to purchase land, before being recovered. In the wake of the Lodha recommendations, it can only be hoped that regional – and also national – governance of Indian cricket will be of a higher standard.

A pair of tots wait their turn in a trainees match Sharda Ugra / © ESPNcricinfo Ltd

Saldanha looks upon the past seven years as an opportunity lost to create a new cadre of young north-eastern players and officials in the interim. The gauche U-16s of back then might well have formed the spine of the senior team today.

Meghalaya was given affiliate status in 2008-09 after fulfilling the BCCI's development and accountability criteria. This has led to greater funding and vibrancy in its cricket. A calendar of coaching and competition for U-16s, U-19s and U-23s was drawn up, with encouragement given to inter-school (U-14) and inter-college cricket. The state, with seven affiliate districts, now has its second turf ground, with two wickets, in Tura in the Garo Hills, and has laid concrete practice pitches in schools in Cherrapunji and Nongstoin.

The Shillong Cricket Academy, inaugurated in June 2012, hires 13 coaches, and has 300 kids in three age groups, from eight to 14. There was unpredecented interest last year, when close to 100 boys turned up for tryouts. Bhattacharjee says, "Parents ask if my children play, what will they get in return? It's professional now." Meghalaya has a scholarship programme for schoolchildren who represent the state, which includes a three-year grant for school material. The idea came from Saldanha's road map.

Bhattacharjee says, "We are already 30-40 years behind. You cannot compare us to Mumbai, who have been playing for hundreds of years. You have to give us an opportunity, you have to give us a structure, and then you see, there will be results."

The next step is to build an indoor facility, where cricketers from across the region can train and play all year round, regardless of the long monsoon months.

It is the administrator's way – of hacking a path through the undergrowth of neglect. The players have their own approach – Smriti Gurung, way ahead of the rest of her class in the U-19s found herself inspired by her novice team-mates, taking their first steps in a cricket. "I learnt determination from them, I've learnt concentration and focus."

Those sceptical about the north-eastern states' fledgling steps in Indian cricket can learn much from Meghalaya's cricket and Gurung's world view. Whether half-empty or half-full, it's always best to find a way to make the glass run over.

The article was first published in ESPNcricinfo written by Sharda Ugra, Senior Editorand TNT- The Northeast Today has not edited any part of this piece

featured image: The scoreboard doubles up as a mini dugout at a schools match at the Nehru sports complex Sharda Ugra / © ESPNcricinfo Ltd