Meghalaya Farmers' Day: Its significance in times of farmer struggles

By Rajat Asthana

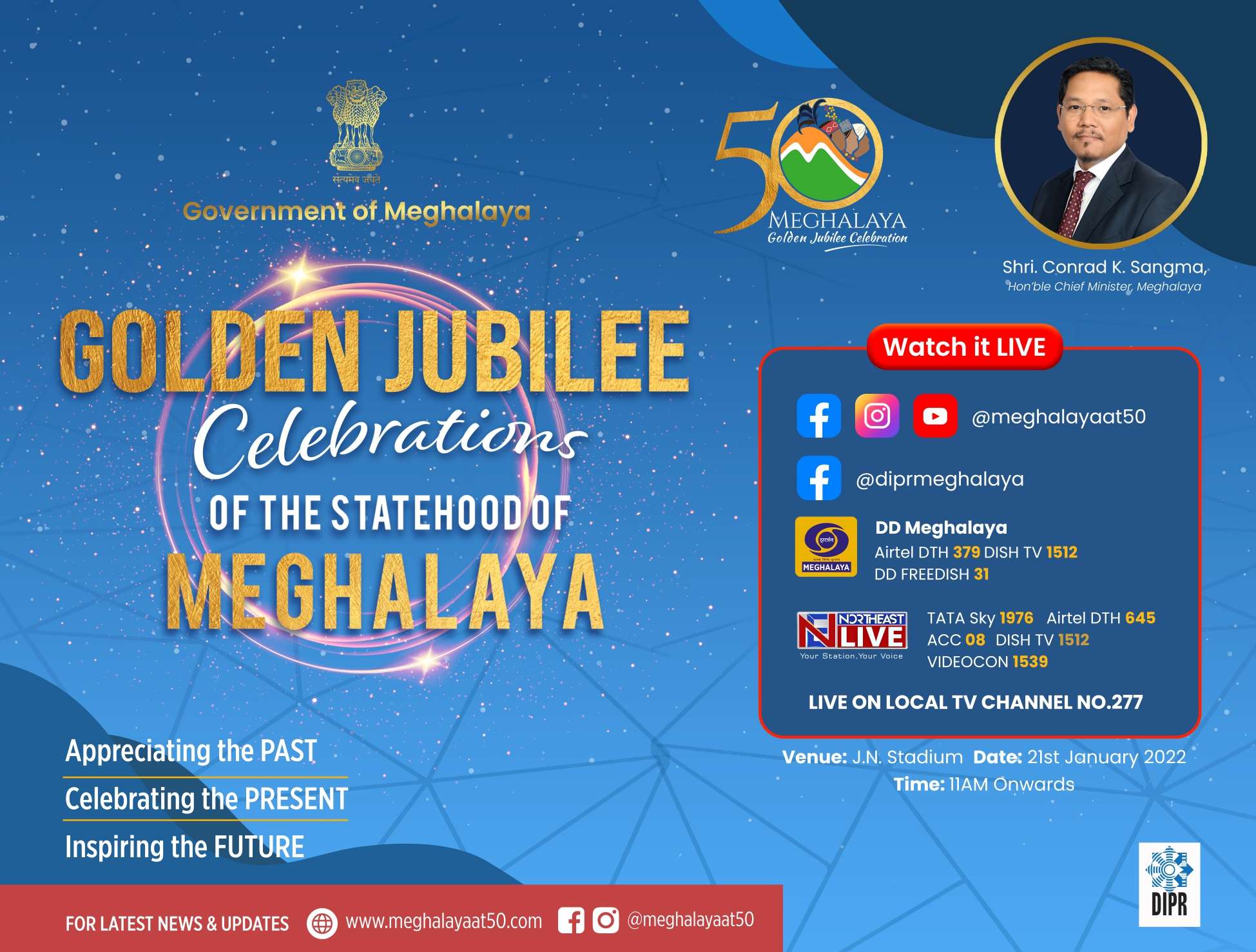

Shillong: Meghalaya today celebrated its second Farmers' Day, after this commemoration was launched exactly 1 year ago by Chief Minister Conrad Sangma, to remember the first Farmers' Parliament held two years ago.

The day is significant as the farmers, during the parliament, presented a charter of demands asking for special funds for introduction of new technologies and the establishment of a farmer commission.

Following this, the NPP-led MDA government brought in the Meghalaya Farmers’ (Empowerment) Commission Act in October, 2019. This provided statutory status to the commission, currently headed by one person.

Significance of the Act

For a state like Meghalaya, the act is significant for the lens it takes for the local farmers for the first time, considering farming is not one of the main revenue providing sectors for the state.

As per the act, the responsibilities of the farmer’s commission include identifying the specific needs of farmers and farming associations, goal setting in the medium and long term, and making suitable policy recommendations to the state government. A salient function of this commission is to suggest measures to secure geographical indications (GI tags) and Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) for high value crops which are unique to Meghalaya.

Furthermore, in September 2020, the government launched a Rs. 200 crore Piggery Mission, aimed at reducing the annual import of pork and improve the incomes of over 25,000 households. Other sector specific initiatives aimed at increasing the value addition include the Jackfruit Mission, the Mushroom Mission, the Milk Mission and the Aquaculture Mission. The Jackfruit Mission especially has seen some success, with products like ‘Jackolate’ and Jack ‘Tikki’ being released into the market.

However, the state marks the second year of Farmer’s Day in a mixed mood, with much hardships faced by farmers due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, the immediate context for Meghalaya’s predominantly small and marginal farmers is still uncertain, especially with the enactment of the three new agricultural laws in September 2020.

The three new farming laws

The Farmers Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Service Act, 2020 creates a framework for contract farming through a written farmer-buyer agreement encompassing the time of supply, quality, grade, standards, price and such other matters While protecting sharecropping rights, it also provides for a three-level dispute settlement mechanism.

The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, 2020 limits the scope of central government intervention for stockholding limits of certain food items only under extraordinary circumstances (such as war and famine), subject to a defined increase in retail price of the commodities. However, the amendment exempts value chain participants in possession of stocks below their installed capacity.

The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020 allows intra-state and inter-state trade of farmers’ produce beyond the physical premises of APMC markets. Further, state governments are prohibited from levying any transaction fee or cess outside the physical premises of the APMC mandis.

How is Meghalaya impacted?

In a telephonic interview with a subject matter expert from North East Slow Food and Agrobiodiversity Society (NESFAS), the risk of commercialization of indigenous agricultural systems in Meghalaya was highlighted. The expert also shed light on the fact that increasing contractualisation could inevitably lead to a risk of monoculture of cash crops, which can pose a threat not only to food security, but also to the biodiversity and climatic resilience of the overall system.

Moreover, the expert highlighted some challenges brought on by the pandemic, and how any moves aimed at privatization or corporatization of agriculture must be carefully thought out on the planks of sustainability and resilience.

Given Meghalaya’s sensitive seismic location and learning from past experiences, the risk posed to the natural ecosystem is many times more.

In conclusion, there is a need to look at agriculture as an investment and not as a balance sheet ‘black hole.’ Moreover, the Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC), a farmer-friendly system with some shortcomings, has to be strengthened for mandis to support the farmers rather than employing a hands-off and de-regulation approach. Finally, capacity building of farmers has to take place for them to practice organic and sustainable farming, a crucial niche for the state of Meghalaya.

(Edited by Anirban Paul)

The author is a postgraduate student of public policy at NLSIU, Bengaluru.