These Naga villagers lead a double life; their ‘king’ eats in Myanmar and sleeps in India

TNT OFFBEAT | June 8, 2018

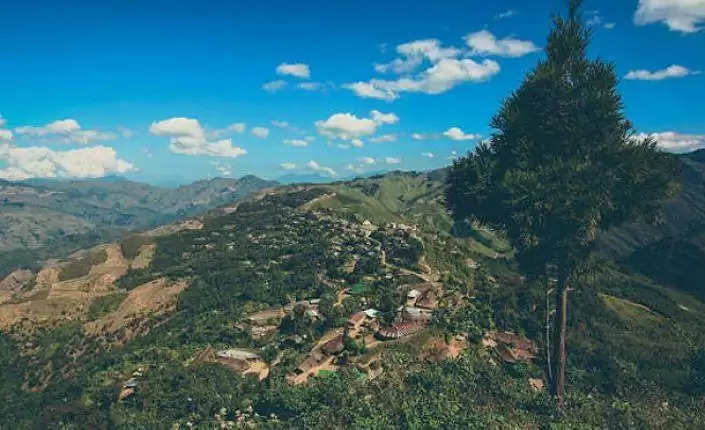

Longwa is a long way from New Delhi. In fact, this remote village in Nagaland is partly foreign territory. It has a 'king' whose household eats in Myanmar and sleeps in India. It has a church, where half the congregation prays on the other side of the border. And its primary school boasts more 'foreign' students than many public schools. India has several soft border points with friendly neighbours, but Longwa in Mon district is unique. Drawn in 1970-71, the international border divides the house of the chief angh — 'king' of 30 villages — into two, with one half in Myanmar and the other in India. "In fact, 26 of the villages under my supervision are in Myanmar," says Tonyei Phawang, 43. He is the 10th angh from his family; some of his predecessors are said to have had as many as 40 wives. Phawang has two. "One of them is from a royal family in Arunachal," says Phawang, who has a badge declaring him to be the chief angh.

Villagers on both sides belong to the Konyak tribe, united by age-old ties. Khampai, a trader says, "Nagas are one people forced into living in two countries and no imaginary line can divide us. All Naga-inhabited territory is one country." Locals from this side go across to fetch firewood, hunt deer and bears, or get opium and cardamom. Opium is in high demand here. Pamsha, in her mid-40s, who makes a living threading necklaces for Konyak women says that with church intervention, opium farming has stopped in Longwa. "But there's a steady supply of kani (local term for opium) from across the border," she says.

In one part of the village, the tarred road acts as the border. Step off it and you are in Myanmar. People from across frequent the grocery stores lining the Indian side of the road all through the day. "About 80% of our customers are Burmese," says a shopkeeper, Manoj Kumar, who came from Churu, Rajasthan two years ago.

Nagas from the Indian side are allowed to travel up to 16km into Myanmar, but villagers say there is no such restriction on the ground. Many have travelled all the way to Yangon, the Burmese capital, without documents. Many Nagas on the Indian side own 125cc Canda two wheelers sold in Myanmar, riding them blithely without registration or number plates.

Life in Longwa goes on as if the border doesn't exist. The local gunmaker, 58-year-old Wangchat, is also the 'gaon bura' or village headman. His shop is on the other side of the border. The cross atop the imposing village church is on the border line too, so only half the building is in India. Dozens of Burmese kids attend Shalom School on the Indian side, as schools in their country are farther.

This free movement has helped facilitate a good-Samaritan effort. For the last three years, Imli Ao, an agriculturist, has been collecting medicines from doctors and health centres in Nagaland and supplying them to needy tribals in Myanmar. He makes Longwa his base camp for the journey — a three-day trek by foot to Montongnukshou village, home to the Leinong Naga tribe in Myanmar. "Those people are much worse off than the poorest people here," says Ao.

Source: TOI